|

How much is required of a man chosen by a god?

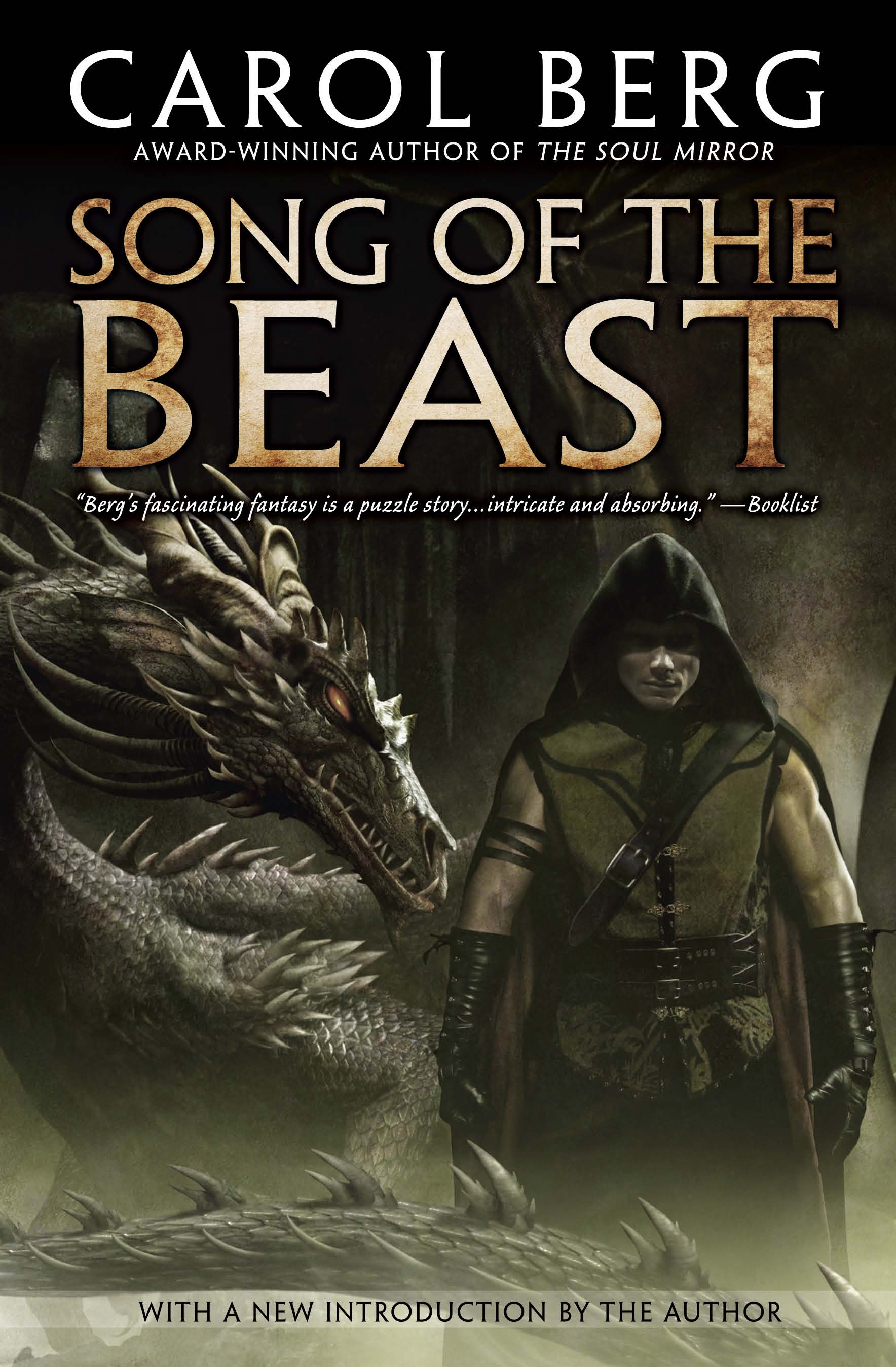

Song of the Beast by Carol Berg

| |

... In the matter of a week, Callia and Narim had me in some semblance of order. I could take a deep breath without passing out, though my constant coughing was a matter of extreme gravity, and a sneeze out of the question. Their modest fare of soup and bread, with cheese added when I could stomach it, was finer than the delicacies of a hundred noble houses where I'd eaten in my youth. I gained a little weight, and Callia said my color was improved a thousandfold-surely her casual habits in matters of undress kept the blood flowing in my face. She brought me a shirt of coarse brown wool and a pair of tan breeches that were immensely cleaner than the rags I'd worn, even a shabby pair of farmer's boots only slightly too tight, "gifts," she said, from one of her admirers. I had not yet convinced myself to speak, a failure which made me feel stupid and weak, just as when I would stand up too long and get shaky at the knees.

Callia left me with far too much time to think about what I was to do with myself. For the last seven years of my captivity I had worked to erase every remnant of my identity, every memory of my past life, every thought, desire, and instinct. Absolute emptiness had been the only way I could fulfill the terms of my sentence, the only way I could be silent, the only way I could survive. I'd had to be unborn. By the end I could sit for days and have no image impose itself on the darkness of my mind, no trace of thought or memory. Now I could not fathom what I was to do next. I began to feel quite foolish that I'd fought so hard to live since my release.

By the middle of the second week, the bump on the back of my head no longer throbbed a warning every time I moved, and I could stand up for moments at a time without falling over, so I picked a night when Callia and the Elhim were both out and started down the stairs. I had depended on the girl's meager livelihood for far too long, yet I didn't have the courage to face her as I took my leave. Halfway to the first landing, the steps dropped out of my vision as if they'd tumbled down a well. My foot could not find a purchase, and I tumbled head first down the stairs. When my cracked ribs hit the splintered wood, I lost track of at least an hour.

Fumbling hands…a knife in my side… "Come on then, arm over my shoulder."

I tried to stay still. Every movement, every breath, sent a lance through my middle. But the hands were insistent and my feet found the steps. Fortunately Callia was the first to discover me, and she hauled me back to her room with many protests of dire offense at my attempt to leave without telling her. "A life for a life," she said. As I could not yet muster words, she made me raise my hand in an oath to stay until she and Narim had judged my condition sound. As she was in the middle of binding up my ribs again, I had no choice but to acquiesce. The swearing was not so difficult as I made it out to be. In truth I was terrified at the thought of leaving Callia's room, and I blessed the injuries that kept me from having to face the world now that I was so irrevocably changed.

Outside of Callia's window was a goodly section of roof, and I'd made it a habit to crawl out onto it whenever anyone came up the stairs. Once Callia went back to work in earnest, she began bringing men back to her room, which sent me out for most of every night. I would lie wedged in a crevice behind a chimney, trying not to listen to what pleasure five coppers could buy. At first the open sky left me sweating with unnamable, unreasoning panic, but after a few nights, I didn't want to go inside any more. As I watched the stars pass over me in their eternal pavane, I began, ever so slightly, to believe that I was free.

One hot, still night as I was sitting on the roof, watching the wedged moon wander in and out among the wispy clouds, Callia climbed out of the window to sit beside me. She carried a linen kerchief, with which she was blotting off the sweat of her most recent encounter, and a flask of wine which she offered to me. I gave her my customary gesture of thanks and drank deep of the sour vintage.

"What do you do out here all night?" she said. "You never seem to be asleep no matter what time it is. You're always just sitting and staring."

I pointed to the dancing moon and the stars, shining dimly in its light, and to my eyes while I held them wide open. Then I pointed to the dark heights where Mazadine lurked, and I passed my hand over my eyes, closing them tight. She had learned to understand my awkward signing very well.

"You weren't allowed to see the sky while you were in prison?"

I waved my hand at the dark, squat houses crowded together in the lane, at the few stragglers abroad, at the shadowed trees of the local baron's parkland across the sleeping city, and the ghostly mountain peaks of the Carag Huim looming on the distant horizon. Then I passed my hand across my eyes again, leaving them closed.

"Nothing. You weren't allowed to see nothing?"

I nodded.

"Damn! I can't imagine it. So I guess you're making up for it out here."

I smiled and returned her flask.

She drank, then peeked over at me sideways with the usual lively sparkle in her eyes. "I've no right to ask it, but I'm devilish curious and not used to minding my own business. Whatever was a Senai doing in Mazadine? I told Narim you must be a murderer at least, for the only thing worse is a traitor and traitors are hanged right off, but you saved my life, and your ways…well, maybe its only they're such gentle ways because you've been in such a wicked state, but I won't believe you a murderer. Are you?"

I shook my head and wished she would stop.

"Then what?" She picked up my knotted and scarred hand and held it in her warm, plump one. "What made them do this?"

I shook my head again, retrieved my hand, and was glad she accepted my difficulty in speaking. Even if I could have convinced myself to say the words aloud, I could only have told her it was to silence my music and thus destroy me. But in a thousand years of trying, I could not have told her why.

Perhaps she thought I was too ashamed to tell her. She didn't press. "You don't mind my asking? I've not offended you?"

I smiled and opened my palms to her, and she passed the wine to me again.

She changed the subject to herself and chattered for half an hour about the peculiarities of men, beginning with her father who began using her when she was eight and selling her when she was nine. Then she branched into detailed comparisons of Senai and Udema and all the others who had the money to pay for their pleasuring. "I think it's why I'm such great friends with Narim," she said. "My other friends ask how I can go about with a gelding child, but I tell them he's the only one I know who's got nothing to gain from using me."

I was listening with only half my attention, happy I was not expected to comment, when there came a low rumbling from the west. As it swelled into an unrelenting thunder, from the western horizon rose a cloud of midnight that quickly spread to blot out the stars in half the sky. Streaks of red fire ripped across the arch of the heavens. The moonlight that flickered behind the looming darkness was carved into angled shapes by ribbed wings that spanned half the city, or was transformed into intricate patterns of green and gold sworls and spirals by translucent membranes. Red fire glinted on coppery-scaled chests so massive they could smother twenty men and horses, and on long tails rippling with muscles so powerful they could knock holes in a granite wall.

"Vanir guard us! Dragons!" Callia dived through the window as the flight passed over Lepan-five or six dragons, soaring on the winds of night. A hot gust lifted my hair, and it was heavy with musk and brimstone, the unmistakable scent of dragon. Soon, from above the blast of flame and the thunderous wind of those mighty wings, would come their cries-long, wailing, haunted cries that chilled the soul, cries that spoke an anger too powerful to bear, deep, bone-shaking roars of fury that caused the enemies of Elyria to cower in their fortresses and bow before the power of our king.

I did not move from my place on the roof, only craned my neck to watch their passing, telling myself every moment to look away-that only danger and grief could be the result of my gaze. Not allowing myself to think-I was well practiced at that-I clamped my arms over my ears. I dared not listen to their cries, but by every god of the Seven, I would not fail to look.

"You're a madman!" said Callia, poking her head out of the window once the sky had regained its midnight peace. "You've been put away too long." She climbed out and plopped herself on the roof beside me. "You never know when one of the cursed beasts is going to glance down and decide you're ugly or insolent or breathing…whatever it is sets them burning. You could have ended up as crisp as Gemma's solstice goose!"

I scarcely heard her. My arms still blocked my ears lest I be undone by the sounds of their passing, and my eyes strained to see the last flickers of their fires as they disappeared in the eastern darkness.

"Are you all right?" The girl pulled my chin around to face her, and her eyes grew wide as she gently touched my cheek. "What in the name of sense…? Whyever didn't you go inside? If you're so fearful of them as to make you weep, then you oughtn't even look."

But of course I had no words as yet, so I could not tell her that my tears had nothing to do with fear.

Return to Song of the Beast

Home

Copyright © Carol Berg, 2024

|